Dogfight: How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution by Fred Vogelstein

I wasn’t surprised to learn that Vogelstein is a writer for WIRED because this book reads like a nicely paced piece of long-form journalism. There is enough historical context to accompany the deeply nerdy stuff so that I didn’t get bogged down with overly technical, dry jargon. Although not particularly revelatory, it was interesting nonetheless to hear the story of the rivalry between Apple and Google framed in the context of the world of mobile devices. I don’t read a lot of nonfiction and even less about singularly contemporary issues, so this is outside my typical sweet spot, but I enjoyed it all the same.

The Bedwetter: Stories of Courage, Redemption, and Pee by Sarah Silverman

So many of my reviews seem to be based on my prior expectations for the book. This is the reason I try not to read anything about a book before I begin it, especially not the back cover summary. Although I like Sarah Silverman and her comedy, my prior experiences with other comedian memoirs presented a fairly low bar for Silverman to hop over. This book is more than just unexpectedly pleasant; it’s also unexpectedly touching and insightful. Silverman writes candidly about her childhood and early career with maturity and in a relaxed way. She’s a grown woman and doesn’t have to tap dance or do bits to entertain you. It’s not stuffed to the gills with jokes and is all the better for that.

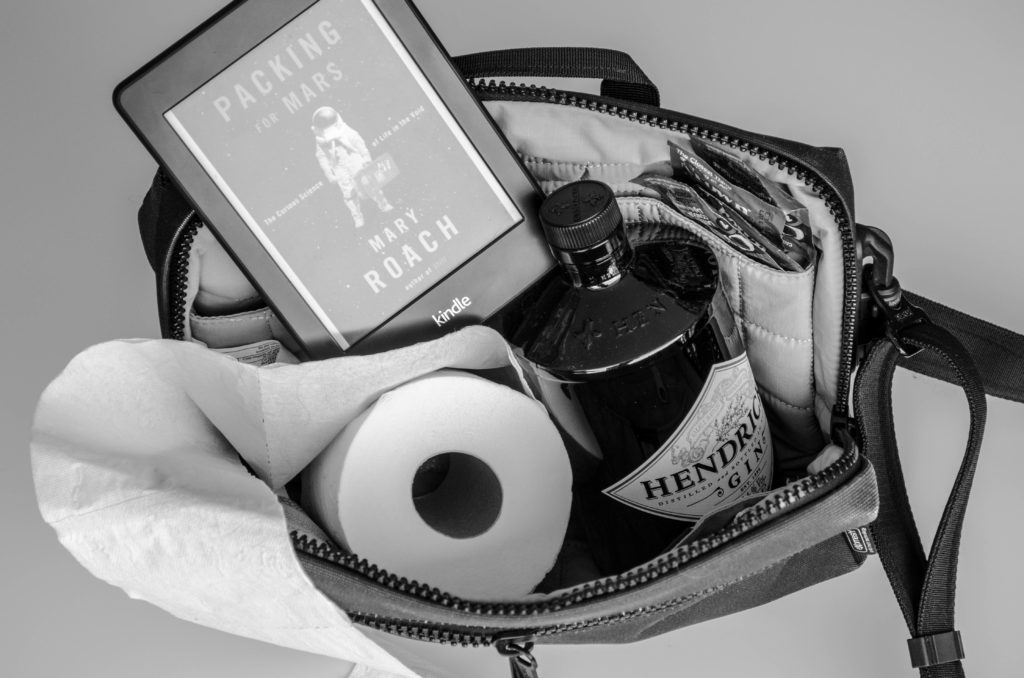

Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void by Mary Roach

I never seem to get tired of Mary Roach’s books, although they all follow roughly the same format: a jokey and light tour through current and foundational research about a topic. In most of Roach’s other books, she takes a relatively simple or pervasive topic or subculture and blows it up, revealing the fascinating world behind everyday things (like Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex or Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal

). Although still enjoyable, sometimes Roach can come off a bit patronizing, particularly in books like Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife

, when she’s interviewing people on the fringes of legitimate science. In Packing for Mars, though, Roach is often the least qualified person in the room, making her a good stand-in for the reader and allowing everyone to marvel at the stuff astronauts have to put up with, fascinating in their mundanity.

No Country for Old Men by Cormac McCarthy

I am a sucker for Cormac McCarthy. His writing style is unique and sparse – a refreshing necessity, sometimes, after reading a bunch of dense and lyrical novels. McCarthy is a master of efficiency and somehow manages to convey characters (and especially sense of place) simply, beautifully and precisely with only the bare bones of language and punctuation. In tone, this book falls somewhere between The Road and the Border Trilogy (All the Pretty Horses

, The Crossing

and Cities of the Plain

). It doesn’t quite reach the fever pitch of tension in The Road, but is still way creepier and foreboding than the expansiveness of All the Pretty Horses. Even if you’ve already seen the movie, I highly recommend this book.

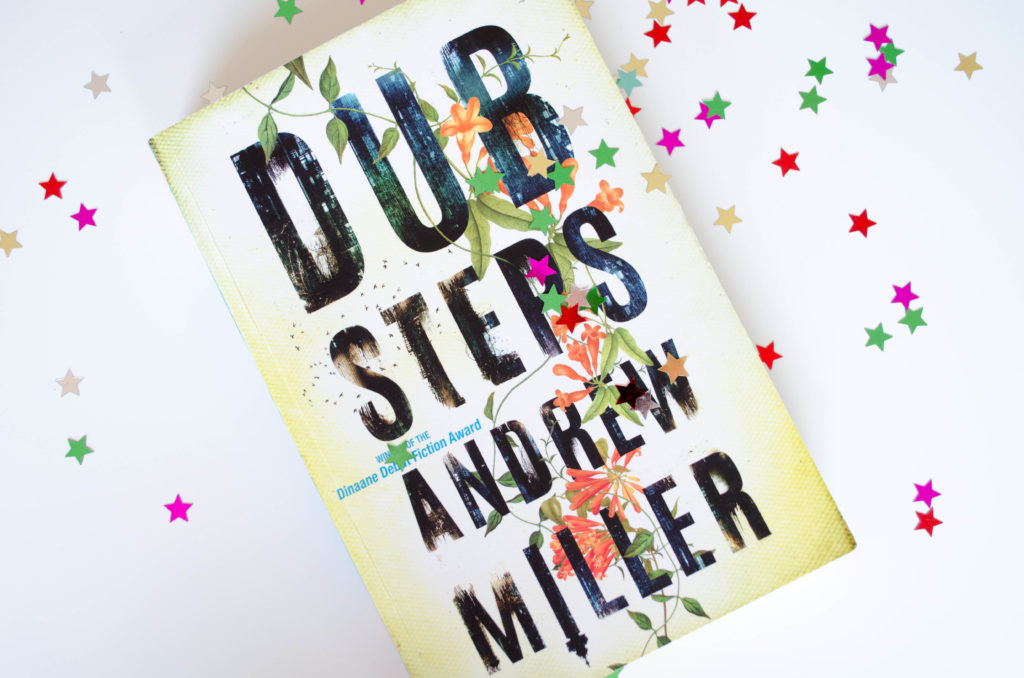

Dub Steps by Andrew Miller

This was a book that I picked up on my recent mini bieb hunting adventure. Miller is a South African poet, and that comes through clearly in this rambling ambitious first novel. The book is divided into several small vignettey chapters that get longer as the book progresses, giving you poetic flashes of the protagonist’s experience as he tries to reckon with a post-apocalyptic Johannesburg. It’s not clear what happened to the rest of the people, but there are plenty of other things going on to keep you distracted from that central mystery. Miller tries to tackle some big philosophical questions about the nature of human relationships, technology, ageing and family and occasionally, almost seemingly by accident, stumbles on some insights. The major flaw of this novel is simply its expansiveness. It tries to do too much and ends up falling short, never really allowing the reader to become attached to any one character or idea.

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

At this point, there isn’t anything insightful I can say about this book that hasn’t already been said more articulately by somebody else. Toni Morrison’s blurb (“required reading”) has exploded and, although I agree with her, I worry people will approach this book with the attitude of taking medicine. I do think every one (at least every American) should read this book, but I hate to think of people opening it begrudgingly. It is challenging (not in a literary sense, but in the sense that it will challenge your notions of race and what it means to be black or believe yourself to be white in America) and heartbreaking, but it’s brilliantly written and I actually think its core message is liberating if not optimistic (it’s not optimistic at all). Coates never explicitly outs himself as an atheist or a nihilist in this book, but those perspectives run powerfully underneath his comments about life inside a black body:

‘The meek shall inherit the earth’ meant nothing to me. The meek were battered in West Baltimore, stomped out at Walbrook Junction, bashed up on Park Heights, and raped in the showers of the city jail. My understanding of the universe was physical, and its moral arc bent toward chaos then concluded in a box.

It’s bleak, sure, but it’s unflinching; I so appreciate his plea to cut away the bullshit, abstractions, aphorisms and “good intentions” of religion, of the notion of a soul, of there being nobility in suffering, and to consider how the construction of whiteness is a constant deliberate physical devaluing of black bodies. I’m still unpacking the complexities and questions in Between the World and Me (and that’s certainly what Coates intended – to ask rather than to answer) and I’m looking forward to reading it again.

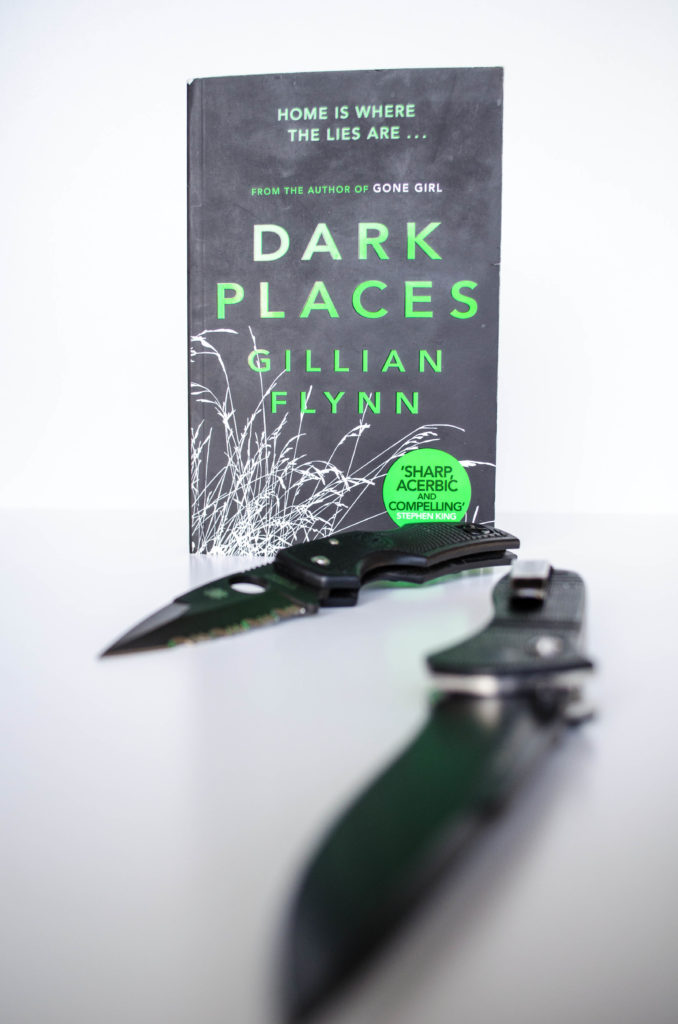

Dark Places by Gillian Flynn

This is the novel that my book club selected for this month, and it taught me something important about myself: I don’t like mysteries. In a TV show or movie, I don’t mind being led by a story through a puzzle that will resolve itself into a neat resolution that can be backed up with specifically identifiable pieces of clues. In a book, however, I find that process maddeningly frustrating and patronizing. To make matters worse, Dark Places is full of unlikeable characters, albeit fairly complex in their despicableness. I know there are people that love that gross-out, torture-porn, cringey tone and enjoy watching horrible people behave horribly; turns out I’m not one of them.

Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell

Like the rest of the world, I was really hot on Malcolm Gladwell for awhile after having read his debut, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. I suppose that distilling complex ideas into simple narratives and metaphors never really goes out of style, but these kinds of books seemed to really have a moment (eg Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything

). If you’re armed with a healthy dose of critical thinking and skepticism, Blink is a perfectly enjoyable collection of stories about subconscious cognitive processing. Gladwell is guilty of egregious confirmation bias and engages in all kinds of logical fallacies, but you don’t necessarily have to approach this book as a scientifically rigorous examination of human psychology. If you read it like you’re listening to an episode of Radiolab and don’t allow yourself to come to any big conclusions about the true nature of the mind, you’ll do just fine.

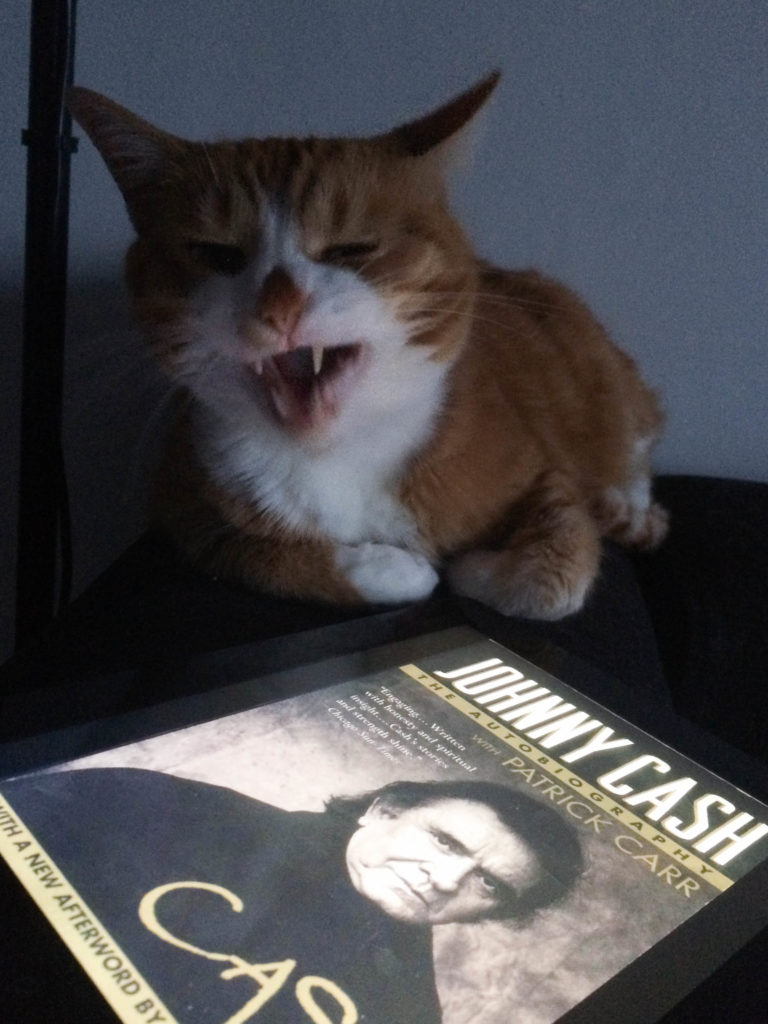

Cash: The Autobiography by Johnny Cash and Patrick Carr

I’d be lying if I told you the movie High Fidelity had no influence on my choice to read this book. Just the way that John Cusak’s character says the words “Johnny Cash’s autobiography Cash by Johnny Cash” was charming enough to stir my interest. I have nothing against the man, but I’m not exactly a fan of Johnny Cash. I know the chorus to Ring of Fire, and the critical reason why that guy shot a man in Reno. Beyond that, I didn’t know much about Cash’s life and career. The style and pacing of this autobiography is both unique and familiar. Unique in that I’ve not read another autobiography that is as rambling as this one, and familiar in that the particular rambling will ring true for anyone that has a grandfather. I don’t know the specifics of the relationship between Cash and his co-author Patrick Carr, but you get the sense that they just sat around and talked, Cash going off on tangents that are as likely to involve eating fried catfish as singing with Elvis Presley. There is an authentic Southernness to this book that I really enjoyed, peppered with unapologetically sincere impressions about the famous people Cash has met (or happens to be related to).

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

I needn’t have avoided this book for as long as I did, because the built up hype did nothing to detract from the quality of the storytelling. I’m a sucker for an emotional World War II narrative, and this book – about a blind French girl and a young German soldier – while not particularly unique or imaginative, has all the ingredients required for just that. I’m not sure if novels about the Holocaust help humanize the otherwise impossible-to-fathom number of people killed, or do the opposite by reducing the genocidal figures in our head down to a more easily understood family unit. I know there’s no reasonable way to tell the story of every person traumatized by war, but I worry sometimes that we desensitize ourselves by narrowing our focus onto a single person or a select few. Maybe there’s no other way to properly process the horror, but it’s necessarily dampened when you only consider the horror of a few people. My digression has nothing to do with this book, though, so don’t let my philosophizing dissuade you from reading it. It’s a nice novel, and well-told. I really enjoyed the prose, and the thread of scientific passion that runs throughout.